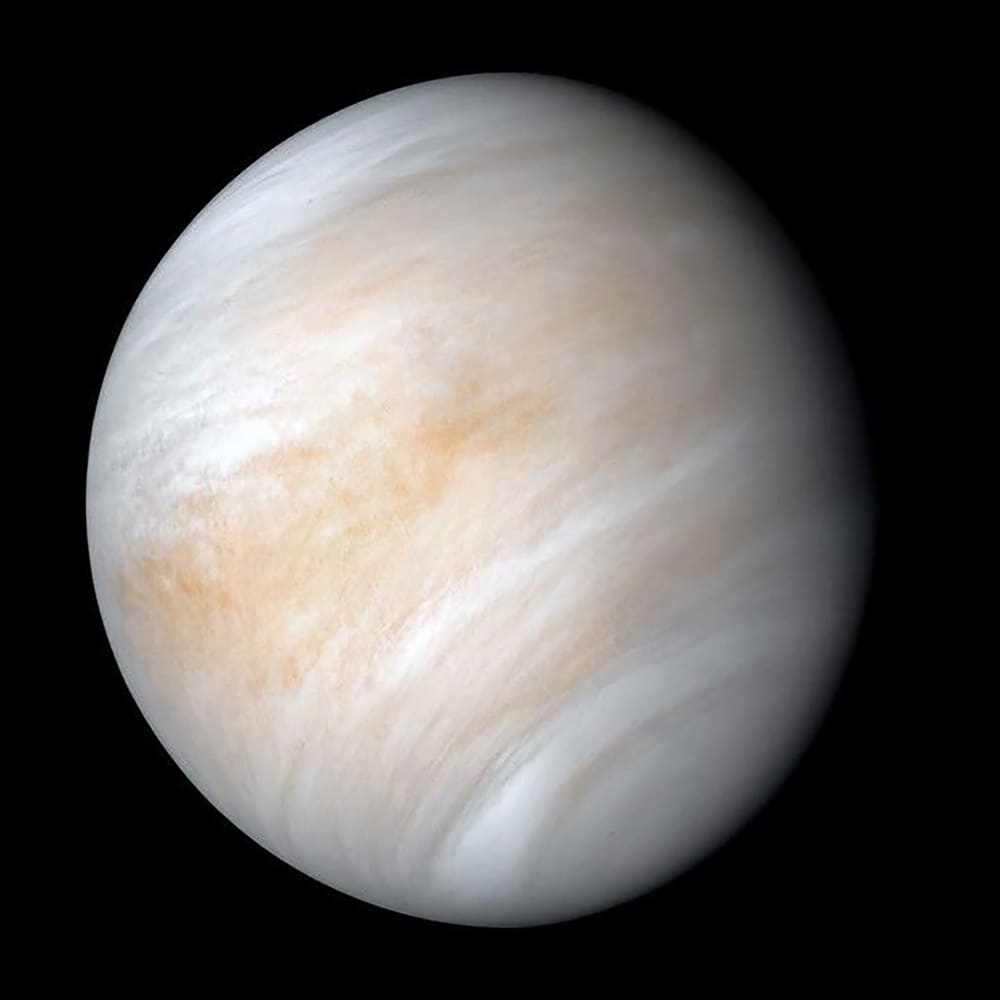

Venus

Venus is the 2nd planet from the Sun and the closet planet to the Earth. Even though it isn’t closest to the Sun, it is the hottest planet because its atmosphere is thick sulfuric acid, which holds in the heat. You can see Venus on many nights, usually early in the morning or early in the evening. When it does appear, it is the third brightest object in the sky.

Years ago, when humans started thinking about going to other planets, Venus was chosen to be first because it was so close. However, once scientists discovered that the atmosphere was so nasty, and the pressure at the surface was very high, they decided that humans couldn’t survive on the sure and we all turned our attention to Mars.

The other weird thing about Venus is that it rotates clockwise. What does that mean? On Earth, we see the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. Of course, the sun isn’t moving, we are. As the Earth rotates, we move away from the sun and then come around to see it again. Because the Earth rotates counterclockwise (the same as most of the planets), we see the sun “coming up” in the east. Ask your teachers or parents to get a basketball and show you how this works. Because Venus rotates clockwise, the sun rises in the morning in the WEST and sets in the evening in the EAST.

How big is Venus compared to Earth?

Venus is almost the same size as Earth! If you could measure all the way around its middle (that’s called the equator), it would be about 7,521 miles (12,104 km) across — Earth’s middle is just a little bigger at 7,926 miles (12,756 km).

How long does it take for Venus to orbit Sun?

A year on Venus (one trip around the Sun) is 225 Earth days long — but here’s the wild part: a single day is even longer! One sunrise to the next takes 243 Earth days. That means the sun would take forever to come back up!

What is the Moon’s surface like?

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and the sixth biggest in our solar system — and the hottest of them all! Wrapped in thick, swirling clouds, it has a rocky, empty surface under a dim, yellow sky.

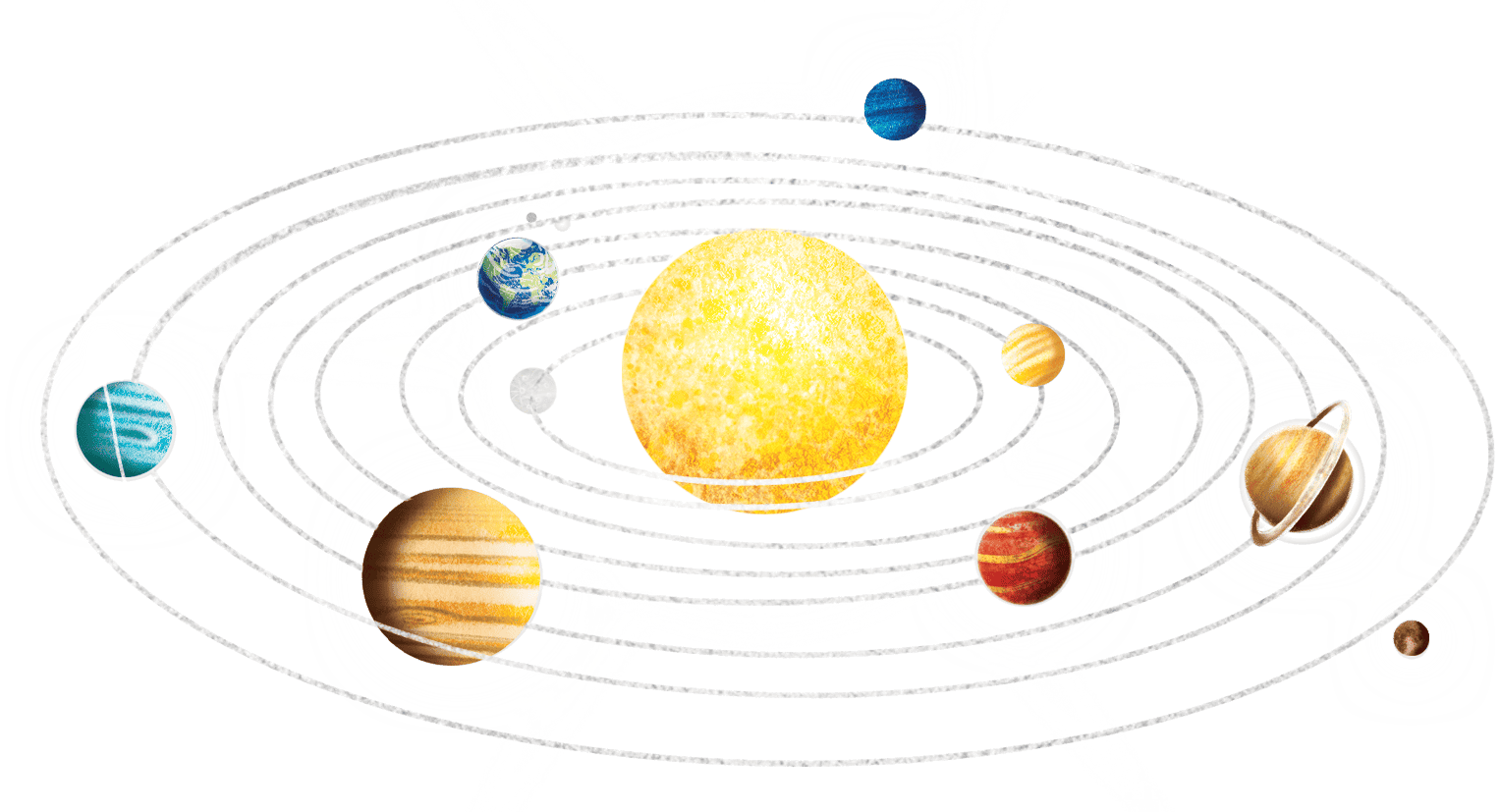

Deep Dive: Astrodynamics

Which planet were our space travelers trying to reach? Why did they miss that planet and end up flying to Venus?

Apollo makes the mistake on page 11, when he says, “We ought to be able to see it [Mercury] and just head that-a-way.” But he corrects his mistake on page 20. “You can’t head that-a-way toward Mercury because it’s moving. You have to head this-a-way and meet Mercury thereabouts.”

Yes, Apollo sounds a bit nutty when he says that, but he is correct. The important part of his statement is that the planets are moving. So, if we aim to where the planet is, by the time we get there, it will have moved, and we will miss it.

It’s sort of like a football quarterback throwing a pass to his receiver. The receiver is running across the field so if the quarterback throws the ball right at the receiver, he won’t be there anymore by the time the ball gets to that spot. The quarterback has to throw the ball where the receiver WILL BE so that he can catch it.

How does the quarterback know where the receiver will be?

- He could calculate it if he knows how fast the receiver runs and the direction he is going. Good college football receivers can run a 40-yd dash in about 4.5 seconds. A good quarterback can throw a football about 55 mph. So, it takes about 1.5 seconds for the football to go 40 yards. So, the quarterback has 3 seconds to escape from the defense and get the pass off. THIS IS RIDICULOUS AND NO QUARTERBACK IN THE HISTORY OF FOOTBALL HAS EVER DONE THIS CALCULATION.

- What they actually do is practice a lot and each player gets to know (with the help of a coach) how the other player runs or throws, etc.

However, space scientists don’t have the opportunity to practice like football players do. So, they have to do that calculation. Actually, the calculation these people must do is much worse.

Calculation Steps

1. Distance Between Earth and Mercury:

The average distance between Earth and Mercury is the difference between their average distances from the Sun:

Distance=rEarth−rMercury=1 AU−0.387 AU=0.613 AU\text{Distance} = r_{\text{Earth}} – r_{\text{Mercury}} = 1 \, \text{AU} – 0.387 \, \text{AU} = 0.613 \, \text{AU}Distance=rEarth−rMercury=1AU−0.387AU=0.613AU

This is the straight-line distance the spacecraft needs to cover.

2. Escape Velocity from Earth:

The spacecraft will need to escape Earth’s gravity and travel through the solar system. This is equivalent to the escape velocity from Earth, which is the speed needed to break free from Earth’s gravitational pull. This velocity is given by:

vescape=2GMEarthrEarthv_{\text{escape}} = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_{\text{Earth}}}{r_{\text{Earth}}}}vescape=rEarth2GMEarth

Where:

- GGG is the gravitational constant (6.674×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−26.674 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \, \text{kg}^{-1} \, \text{s}^{-2}6.674×10−11m3kg−1s−2)

- MEarthM_{\text{Earth}}MEarth is the mass of the Earth (5.972×1024 kg5.972 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg}5.972×1024kg)

- rEarthr_{\text{Earth}}rEarth is the radius of Earth’s orbit (1 AU)

The escape velocity at 1 AU is about 42.1 km/s.

3. Transfer Velocity:

After the spacecraft escapes Earth’s gravitational influence, it follows a hyperbolic trajectory. For the spacecraft to move directly from Earth to Mercury, it would need a velocity that’s higher than the Earth’s orbital velocity. This is the initial velocity required to follow a hyperbolic escape trajectory. In practice, this is a “delta-v” (change in velocity) from the Earth’s orbit, and we assume it would be added to the spacecraft’s speed to overcome the Sun’s gravitational pull.

The spacecraft needs enough energy to travel this 0.613 AU distance toward Mercury. The exact velocity needed will depend on the mission parameters, but a typical value might be about 2.5 to 3.5 km/s beyond Earth’s orbital velocity, depending on the mission profile.

4. Time to Reach Mercury:

The time required to get from Earth to Mercury will depend on the spacecraft’s velocity. A simple estimate would involve dividing the distance by the spacecraft’s velocity. Assuming an average velocity of 25 km/s (a rough estimate for a fast interplanetary mission), we can estimate the time as:

t=DistanceVelocity=0.613 AU25 km/st = \frac{\text{Distance}}{\text{Velocity}} = \frac{0.613 \, \text{AU}}{25 \, \text{km/s}}t=VelocityDistance=25km/s0.613AU

Converting AU to kilometers (1 AU=149.6×106 km1 \, \text{AU} = 149.6 \times 10^6 \, \text{km}1AU=149.6×106km):

t=0.613×149.6×106 km25 km/s≈3.66 dayst = \frac{0.613 \times 149.6 \times 10^6 \, \text{km}}{25 \, \text{km/s}} \approx 3.66 \, \text{days}t=25km/s0.613×149.6×106km≈3.66days

Summary:

- Distance: 0.613 AU (about 91.7 million km)

- Escape velocity from Earth: 42.1 km/s

- Transfer velocity: Approximately 2.5 to 3.5 km/s faster than Earth’s orbital velocity

- Travel time: About 3.66 days at a velocity of 25 km/s

This is a simplified approach, assuming a direct, unencumbered path from Earth to Mercury.

Calculation Steps

1. Distance Between Earth and Mercury:

The average distance between Earth and Mercury is the difference between their average distances from the Sun:

Distance=rEarth−rMercury=1 AU−0.387 AU=0.613 AU\text{Distance} = r_{\text{Earth}} – r_{\text{Mercury}} = 1 \, \text{AU} – 0.387 \, \text{AU} = 0.613 \, \text{AU}Distance=rEarth−rMercury=1AU−0.387AU=0.613AU

This is the straight-line distance the spacecraft needs to cover.

2. Escape Velocity from Earth:

The spacecraft will need to escape Earth’s gravity and travel through the solar system. This is equivalent to the escape velocity from Earth, which is the speed needed to break free from Earth’s gravitational pull. This velocity is given by:

vescape=2GMEarthrEarthv_{\text{escape}} = \sqrt{\frac{2GM_{\text{Earth}}}{r_{\text{Earth}}}}vescape=rEarth2GMEarth

Where:

- GGG is the gravitational constant (6.674×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−26.674 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \, \text{kg}^{-1} \, \text{s}^{-2}6.674×10−11m3kg−1s−2)

- MEarthM_{\text{Earth}}MEarth is the mass of the Earth (5.972×1024 kg5.972 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg}5.972×1024kg)

- rEarthr_{\text{Earth}}rEarth is the radius of Earth’s orbit (1 AU)

The escape velocity at 1 AU is about 42.1 km/s.

3. Transfer Velocity:

After the spacecraft escapes Earth’s gravitational influence, it follows a hyperbolic trajectory. For the spacecraft to move directly from Earth to Mercury, it would need a velocity that’s higher than the Earth’s orbital velocity. This is the initial velocity required to follow a hyperbolic escape trajectory. In practice, this is a “delta-v” (change in velocity) from the Earth’s orbit, and we assume it would be added to the spacecraft’s speed to overcome the Sun’s gravitational pull.

The spacecraft needs enough energy to travel this 0.613 AU distance toward Mercury. The exact velocity needed will depend on the mission parameters, but a typical value might be about 2.5 to 3.5 km/s beyond Earth’s orbital velocity, depending on the mission profile.

4. Time to Reach Mercury:

The time required to get from Earth to Mercury will depend on the spacecraft’s velocity. A simple estimate would involve dividing the distance by the spacecraft’s velocity. Assuming an average velocity of 25 km/s (a rough estimate for a fast interplanetary mission), we can estimate the time as:

t=DistanceVelocity=0.613 AU25 km/st = \frac{\text{Distance}}{\text{Velocity}} = \frac{0.613 \, \text{AU}}{25 \, \text{km/s}}t=VelocityDistance=25km/s0.613AU

Converting AU to kilometers (1 AU=149.6×106 km1 \, \text{AU} = 149.6 \times 10^6 \, \text{km}1AU=149.6×106km):

t=0.613×149.6×106 km25 km/s≈3.66 dayst = \frac{0.613 \times 149.6 \times 10^6 \, \text{km}}{25 \, \text{km/s}} \approx 3.66 \, \text{days}t=25km/s0.613×149.6×106km≈3.66days

Summary:

- Distance: 0.613 AU (about 91.7 million km)

- Escape velocity from Earth: 42.1 km/s

- Transfer velocity: Approximately 2.5 to 3.5 km/s faster than Earth’s orbital velocity

- Travel time: About 3.66 days at a velocity of 25 km/s

This is a simplified approach, assuming a direct, unencumbered path from Earth to Mercury.

What does all that really complicated math mean?

In the simplest terms we need to know where Mercury is now and where it will be by the time we get there in our ship.

Here are the steps:

1.

How far apart are the two planets when we are leaving Earth?

2.

How fast can our ship go?

Therefore, how long will take to get to Mercury?

3.

How fast does Mercury travel in its orbit?

Therefore, how far will Mercury have moved in time it takes our ship to fly there?

4.

Now we know the new direction to go, but…

5.

We also have to recalculate how long it will take to get to the new location of Mercury because it is going to be slightly different than the old calculation.

The people who do all of this are REALLY SMART! That’s why we call them “rocket scientists.”

The scientists who do all this work are called astrodynamicists. Cool job title. Do you want to go into the field of astrodynamics and plan missions to other planets? These scientists study the motion of objects in space, including planets, moons, comets, asteroids, and spacecraft. Astrodynamicists use the principles of orbital mechanics to calculate trajectories (the direction to fly), optimize flight paths, and determine the necessary velocities (how fast to go) and burns (this is what makes them go fast) for spacecraft to travel between planets or moons.

So, if you want to go anywhere in space, you better get to know an astrodynamicist (right now I’m still working on pronouncing the word).

WHEW!!!

Are you ready for an Out Of This World Adventure?

-

Sale!

Cosmic Collection: Books 1–3 (Hardcover)

Original price was: $75.00.$67.50Current price is: $67.50. -

Sale!

Cosmic Collection: Books 1–3 (Paperback)

Original price was: $45.00.$40.50Current price is: $40.50. -

Skyler’s Space Adventures: An Unexpected Encounter (Hardcover)

$25.00 -

Skyler’s Space Adventures: An Unexpected Encounter (Paperback)

$15.00